The visitor will notice right away that the photograph at the top of Bidú’s page has not been cropped to highlight the subjects and do away with “unnecessary” background the way almost all others on this website have been. This is a deliberate choice. The image, exactly as framed, preserves the ambience of a special place on a special occasion, with its view of an ornate, tarnished staircase railing, faded gold wallpaper that was doubtless once the height of fashion, a wainscoted passageway leading to heavy mahogany (or walnut) doors that open into yet more paneled spaces redolent of a bygone era of Upper Eastside Manhattan affluence, and the more mundane matter of folding chairs stacked up after providing seating for an important event. The venue is the Columbus Club, the occasion the great dinner party that celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of Bidú’s and my dear friend Licia’s American debut at the Metropolitan Opera. The Club—a virtual warren of rooms large and small (even tiny) of myriad shapes, passages of odd lengths and configurations, staircases long and short (whether circular or direct), with landings and windows and full columns and fluted pilasters in unexpected places—was obviously once the elegant residence of a wealthy family, and it contained more than enough inside area to house several generations at the same time both on a high level of personal comfort and with adequate privacy. In its “converted” state, it was a great place to “hang,” whether or not one was Italian or a Cavaliere di (Cristoforo) Colombo. How many wonderful meals were happily consumed with how much wine in the little dining room there! Licia and Joe were sustaining members of the organization, to put it mildly, and one had only to appear as their guest to be treated royally.

On the third floor, reached by one of the smaller, “back-of-house” staircases, there was a landing that incorporated a little alcove. This unusual space was somewhat hidden around a sharp corner and was not instantly obvious to anyone using the stairs in either direction. Within the alcove there was a small bench. When things got too boisterous or tiring or just plain hot (in temperature) downstairs, Bidú would likely be found seated alone on that little bench in that alcove, fanning herself with a small, chic little fan that appeared to have ivory or alabaster ribs and to be, perhaps, an heirloom (this is possibly the special prerogative of a Brazilian lady; I never knew another woman who regularly carried a fan in her purse). I discovered her there quite by accident one day when climbing away from the noise and heat myself. She put a conspiratorial index finger to her lips and motioned me to sit down next to her. That first time, at the moment we decided we might be missed and a search party sent out (thus revealing the little “secret place” if we were found), she said, referring to inevitable future times at the Club, “Eef I deezappear, you weel know where I am. Come to me then.” I did, and there, over the years, we enjoyed some of our sweetest conversations.

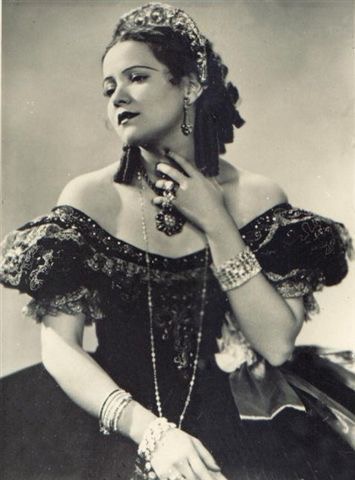

Balduína de Oliveira Sayão was born into a cultured if not aristocratic family in the Botafogo district of Rio de Janeiro. The matter of her age was ever a bone of contention with the dear lady. Reference books uniformly give her year of birth as 1902, though she strenuously insisted it was 1904 (“Reeelly, reeelly, eet eez!!”), which is in fact the year stated in the Social Security Death Registry. Regardless of which date is accurate, when looking at her above I defy anyone to decide that she is anywhere near either eighty-six or eighty-eight, one of which had to have been the case.

Her father died when she was five. Certain of her colleagues (whose identities I’ll protect here) posited that as the reason she chose much older husbands. The first, Italian impresario Walter Mocchi, was more than three decades her senior. That union didn’t endure. Her second marriage, the one that “took” and lasted from the mid-1930s until she became a widow in 1963, was to the very great Salerno-born baritone Giuseppe Danise, twenty (or twenty-two!) years older than she.

Bidú (perhaps no diminutive has ever been more perfectly matched to its bearer) liked very much that I was a sincere admirer of Danise’s recordings and could talk about them intelligently. That’s how we first hit if off. She (like Zinka) didn’t live in the past the way many of her diva peers did, and she found it difficult to listen either to her own recordings or those of her husband. “That was a long time ago,” she said frequently. When she retired, she truly retired: no teaching, no master classes, no singing for fun or friends or charity—finita! She couldn’t understand why some of her colleagues went on singing long past their best years, displaying voices suffering from the ravages of age: pitch troubles, breath troubles, general tonal decay, screeches for high notes. The inability of an aged great singer to relinquish the spotlight was often painful to witness. Bidú’s evaluation: “Eet’s a seeckness, eet’s a seeckness!” Such commentary was often delivered sotto voce into my ear when she sat in a chair at the bass-clef end of the keyboard while I was playing for such an aged colleague in informal circumstances. It wasn’t always easy to go on doing what I was doing with a straight face!

It was a delicate matter to draw forth from Bidú any observations about her early years, but the rewards were great if she could be gotten, however briefly, to speak of her lessons with Jean De Reszke, the greatest tenor of the generation just before Caruso’s and an artist of legendary accomplishment and stature. They worked together for several years (“In Nice, not Paris,” she always stipulated) until his death in 1925. De Reszke’s tutelage, and later that of her husband (who in retirement became one of the world’s foremost vocal pedagogues), together with her own intelligence and common sense, made it possible for Bidú’s small but lovely voice to survive the rigors of an international career on the stages of opera houses that would on sight have seemed inclined to swallow it up. Despite not being voluminous, because it was superbly produced and on the breath it carried supremely well, allowing her the freedom to exploit every facet of her beguiling presence and personality, in the process winning the hearts of opera lovers everywhere. A certain vocal “fragility” is evident in her recordings and on tapes of her Met broadcasts, though at the same time there is a surprising core of tensile strength in the tone that clearly indicates the will of a diva. I once said to Licia that I thought perhaps Bidú’s voice had been somewhat small for Violetta in a cavern the size of the Metropolitan. Licia didn’t contradict me, but said immediately, “Ah, but Bidú’s Violetta had-a such a beauty.”

As Violetta in La traviata

Regarding the size of her voice and the limitations it imposed upon her, Bidú would say, with a great air of sacrifice and loss (and a heavy sigh for good measure), “My life was renunciation upon renunciation.” If I heard that statement once, I heard it fifty times. She would have loved to sing Butterfly, Manon Lescaut, and Tosca, but those, she said (anticipation of this quotation is the reason I gave her full birth name above), were roles “for a Balduína, and I am a Bidú.” Perhaps one ought not parse that little dictum too carefully for the ultimate in logic; its meaning is perfectly clear.

Others thought so highly of her temperamental suitability for those forbidden roles that from time to time a fan imagined he had witnessed her do one of them. Once, she and I were seated together on a bench in the east end of the Metropolitan Opera House lobby, chatting while waiting for a friend to join us and go to lunch. One of the known denizens of the standees line, a grizzled and wizened little man, neither well-dressed nor kempt, came up and asked, “Oh, Miss Sahyoo, would you give me your autograph? I just loved you, ‘specially your Butterfly.” From a ragged pocket, he produced a pathetic little scrap of paper, which he handed to her. Turning to me, he asked, “You got a pen, buddy?” I produced one. Bidú charmingly informed him that she was delighted he remembered her and enjoyed her singing but that, in fact, she had never sung Butterfly. He disagreed at once: “Oh, yes, I saw your Butterfly lots of times, and I loved it.” She remained as sweet, friendly, and polite as before in her somewhat more emphatic second denial: “No, I’m so sorry, I would have loved to do Butterfly, but I never could, she was too heavy for my voice.” In an instant, the poor fellow went from zero to ten on the outrage scale. “Listen, lady, you did so sing it. You may not remember it, but I do, and it was [expletive] great!” With that, he snatched the paper from her hand (she had signed it) and stormed off. There was nothing to say, on the spot, about such an incident. Bidú, her huge dark eyes seeming even bigger than usual, just silently handed my pen back to me and took up the conversation where it had been when “Mr. Butterfly” (as she called him ever after) approached her.

She did have a rarely seen territorial streak that seemed very much to conflict with her outwardly rather placid offstage manner. When the wonderful Brazilian soprano Neyde Thomaz came to the Met for a debut as Zerlina in 1963 and demonstrated a voice more substantial but just as beautiful as Bidú’s, a personality of equal charm and appeal, and a physical presence that was utterly delightful (she had a gorgeous face and petite but voluptuous figure), Bidú was not amused and reacted poorly indeed. She refused to meet or congratulate the newcomer. In this behavior, she replicated that of her own great predecessor, Lucrezia Bori. Miss Bori, though a Spaniard and not Brazilian (the shared Hispanic background, regardless of national identity, was evidently enough to provoke jealousy) also suffered from a grave lack of delight when the young Bidú, Massenet’s Manon to the very life, made her Met debut in that role and conquered all hearers. Bori, foremost Manon of her generation, had retired just a year earlier. Considerations of rivalry and status remain eternally powerful elements in the psyche of a diva. Fortunately for Bidú, she lasted more than long enough in New York to count Bori as a close friend and, indeed, admirer. Poor Neyde had no such extended opportunity to effect the same conciliation. Bidú had at least a single regret vis-à-vis one of her best friends, too. Once she said to me, “They [the Met] should have given me Lauretta, not Licia. Or at least both of us!” She got no argument from me on what was an entirely reasonable artistic notion. I might have added “Nannetta, too!” And I did mean that the public should have had the opportunity to hear them both in those roles, just as it did with Susanna, Violetta, and Mimì.

Like Mme Pons, Bidú, too, was honored with a postage stamp. Whereas the great Lily’s was issued by her adopted country (to my knowledge, France has never paid that particular tribute to her), Bidú’s was put out by her native Brazil. (I can hear her now, offering her standard native-speaker-of-Portuguese corrective to American friends: “Yes, you can say it that way, but you must spell it with the ‘s’!”) Matters of elocution and orthography aside, the stamp is a lovely one, certainly in its spirit. Rio’s Teatro Municipal and the new Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center (where Bidú never appeared except as a member of the audience) surround the image of the little soprano. Too bad that unlike the Pons stamp, and though it is a rendering of a famous photo of Bidú as Violetta (see above), the postal portrait bears no genuine facial resemblance to its subject. Never mind. Hardly any of her compatriots of younger generations would know the difference, though some may actually be aware that Carmen Miranda was not the only important Brasilian (there, I’ll spell it correctly for her at least once!) singer of her time, that there was someone else of note whose name perhaps a select few of them just might have on the tips of their tongues.

Every now and then, listening to the recorded singing of one of our friends, or to some selection that one of them—and not necessarily an older one—sang to my accompaniment in her presence, I will think I feel that little sweet rush of air at my left ear that contained a priceless Sayão jewel of a comment that I could never, ever repeat, except in the most non-specific and general terms possible, to another soul.